A Recession by Any Other Name?

August 5, 2022

To Inform:

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” This line from Romeo and Juliet highlights a very important principle – what matters is what something is, not what it is called. There’s been some debate over the meaning of the word “recession” over the last week as the US clocked its second quarter in a row of negative GDP growth. While long understood to be a signal of recession, two negative quarters of GDP growth is not consistent with the definition of recession as laid out by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The NBER is the official scorekeeper when it comes to calling recessions, which they define as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.” So, debate aside, is this a recession? To borrow from Shakespeare, are we in a recession, regardless of what the scorekeepers want to call it?

So far, I think the answer is no. While GDP has contracted, we must be intellectually honest by looking at the rest of the economy. The NBER looks at a number of indicators including employment data, growth in real personal income, and industrial production. Starting with employment, it’s important to note that in the post-WW2 era, every recession has been marked by a substantial increase in unemployment. The chart below from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis captures the 12 recessions since WW2 along with the rate of unemployment. The average increase in unemployment in 11 of the 12 (ignoring the highly anomalous 2020 data) was 3.4%. With today’s July employment report seeing over 500,000 jobs added last month, we sit at 3.5%, levels not indicative of recession.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Real personal income growth has slowed, but is not in marked decline as is typical in a number of recessions since the 1970s.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Industrial production isn’t showing any cracks at the moment as manufacturing data remains in expansion territory.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

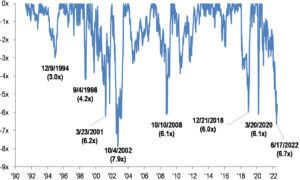

So, why have stocks sold off so much this year if we aren’t in recession? The story for much of the decline seen in stocks year-to-date has been falling price-to-earnings multiples. Investors simply are refusing to pay as much for a dollar of earnings as they were a year ago. Rising interest rates, concerns over peak earnings, and fears of recession have all contributed to this year’s decline in earnings multiples. As of mid-June, before the recent rally, forward earnings multiples (the multiple the market is attaching to the next 12 months of earnings estimates) had fallen almost 7 points YTD.

Source: JPMorgan

Fuel for this most recent rally is likely interest rates easing since mid-June, commodity prices pulling back, and recession fears perhaps ticking marginally lower. In a number of portfolios we have the privilege of managing for clients we were marginal buyers of stocks and bonds at the end of Q2. The trough in sentiment and markets seemed to be too big to ignore. The business of calling recessions and adjusting portfolios is fraught with the potential for making mistakes. Our goal is to check our emotions at the door and look to the data, adjusting portfolios as appropriate. Borrowing from Shakespeare again, it’s fair to say that there are things about the economy that stink right now (lousy consumer confidence, tighter monetary conditions) but the smell of recession isn’t yet in the air.

![]()

Written by Alex Durbin, Portfolio Manager