The Bond Math, Deficits, and “One Big Beautiful Bill”

May 23, 2025

To Inform:

It’s hard to believe how quickly things are moving in Washington, D.C. As I type this, Travis Upton, CEO of The Joseph Group, is barreling down on the city in a tour bus, accompanying a gaggle of high school choir students. I can’t help but wonder if he also attempts a little bit of shoe leather work in the nation’s capital. The talk of D.C. right now and in financial markets is the tax bill working through Congress and its concomitant impact on financial markets, particularly the bond market.

Let’s start with what is being discussed with the tax bill. The tax bill extends the cuts that were enshrined in law in 2017 but also has a few new twists. The bill includes no income tax on tips and overtime, deductibility of auto loan interest, an increase in the state and local tax deduction (SALT) to $40,000 from $10,000, and a host of measures to stimulate business investment. Cuts to Medicaid and clean energy provisions from the Inflation Reduction Act, along with expected tariff revenue are the “payfors.”

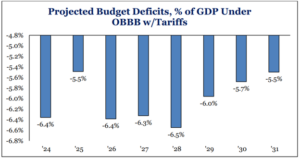

While the bill doesn’t make the deficit worse, it doesn’t make it any better, either. Researchers at Strategas project budget deficits to continue at around 6.5% of GDP until 2029, where they fall to below 6%.

Source: Strategas

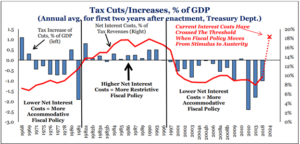

Market reaction to this bill has been mixed. Stocks generally have seemed to rally on the stimulative nature of the bill, but bonds have been taken to the woodshed. Why, you ask? Well, we’re in somewhat rare territory. The chart below, also from Strategas, shows data going back to the late 1960s. Captured in the blue bars are the magnitude of various tax bills. When above the horizontal black line that indicates a tax bill that raised taxes. When below the horizontal black line that indicates a tax bill that reduced taxes. Since the late 1990s, it appears both sides of the aisle in Washington have found it much easier and rewarding to cut taxes than to raise them. This is an easier sell when interest costs as a percentage of tax revenues (the red line) are low. They aren’t low today. Interest costs are now nearly 20% of what the government takes in, up from around 8% in 2013.

Source: Strategas

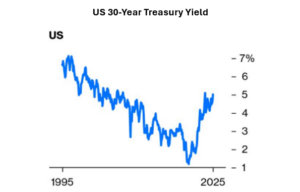

What does this all mean for bonds? It means more treasury bond issuance. Lots of it. Over the long run, this would argue for higher interest rates, all else being equal. The market is moving in this direction, with the yield on the 30-year US Treasury Bond moving above 5% this week, a level not seen consistently since the early 2000s.

Source: Bloomberg

As a reminder, when bond yields go up, bond prices go down. No one felt that more acutely than investors in the 100-year bond issued by Austria in 2020. With a yield at issue of just 0.85%, investors in this bond saw its price plummet 75% over the last five years as interest rates there are now pushing 3%.

And that brings me to my final point as it relates to bond math. The time to really worry about bonds is when rates are low. The “cushion” low interest bonds provide should rates go up is very limited compared to the cushion provided by bonds with higher coupons at issue. Investors in bonds today may not enjoy the kind of near double-digit price returns seen in 2019 and 2020 when interest rates were falling. Why not? I believe the likelihood for interest rates to go back to those levels in an era of higher deficits and higher treasury bond supply is very low. That said, for investors satisfied by holding bonds for their income potential, yields at 5% today are interesting.

Investors have very little control over what happens in Washington. Some reading this may wish the government was more serious about reducing deficits and putting this country on a more sound financial footing. Perhaps rising bond yields in the U.S. convince lawmakers of the need to both spend and raise revenue efficiently. Perhaps, as bond yields get uncomfortably (for the borrower!) high, that day is coming sooner than we think. In the meantime, “the math” on government bond yields at around 5% may provide some solace.

Written by Alex Durbin, CFA, Chief Investment Officer