On Trees Growing to the Sky

August 30, 2024

To Inform:

First, let me ask for your forgiveness for finding another way of incorporating trees into a Wealthnotes topic (no pictures this time). That said, the expression, “trees don’t grow to the sky” was mentioned in a meeting I had this week with a sales representative from a mutual fund firm and then in article written by a Bloomberg columnist (there must be something about trees). Simply put, this expression in an investment context means the stuff that’s been going up lately doesn’t always keep going up at the same rate in the future.

We’ve talked about this concept in different ways in the past using different examples, but the moral of this story is one worth returning to. The temptation to believe trees do grow to the sky is one that is hard to resist, especially when it seems like that is in fact what they are doing. I remember meeting with a client earlier this summer who expressed an interest in a company whose stock has performed fantastically well over the last several years. I told this client that the likelihood that this company can do again what it has done over the last few years is almost impossible. Just as a tree reaches maturity, companies often reach peaks either in terms of their competitive position, their valuation (what people are willing to pay for the company), or both.

We also see these peaks at the index level. Over the years Travis and I both have referenced the cyclicality in markets and the potential for disappointment if one assumes that the trees that have been growing the highest lately are “growing to the sky.” We’ve suggested that at times there are better value trees out there with a lot more potential than the ones everyone has been talking about.

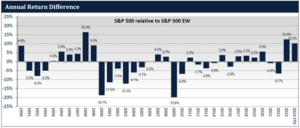

One way to look at this is to consider the relative performance between the S&P 500 Index (which puts the heaviest weights on the biggest companies) and the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index. Both indexes hold the same stocks, but the equal weight index holds them all at equal weights of 0.20%. After a historically wide gap in 2023 (with equal weight underperforming), 2024 has continued the trend of equal-weight underperformance. If the year simply ended on June 30, it would have been the 3rd worst relative year for the equal weight index in the last 35 years. The last time this happened, the S&P 500 was in the final stages of the Tech Bubble.

Source: Lyrical Asset Management

While I am not making the claim that today speculative fervor in the US stock market matches that of the late 1990s, I do find it worth considering what has happened in the past after these streaks of relative outperformance by the S&P 500 compared to the equal weight index.

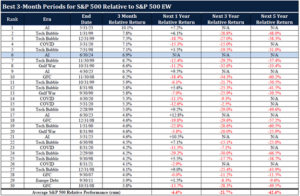

The table below has a lot going on, but the message is pretty simple. The 30 “episodes” below are the 30 best 3-month periods for the S&P 500 relative to the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index. As you can see, the end of June was the 6th best 3-month period out of a total of 412 of them since 1990. What have investors experienced in the next 1, 3, and 5-year periods? The table is pretty clear. On average, the S&P 500 has underperformed the equal weight index by 4.4% over the next year, by 21.7% over the next 3 years, and by a whopping 42.4% over the next 5 years.

Source: Lyrical Asset Management

What’s even more striking is that compared to a measure of the cheapest stocks in the S&P 500, the numbers are even greater. Instead of comparing the S&P 500’s performance to the equal weight index, the S&P 500 compared to the cheapest 100 stocks in the S&P 500 shows an average relative underperformance of 110% over the ensuing 5-year period. In other words, buying low still makes sense over the long-term even if it feels like other stocks will “sell high” into perpetuity.

We don’t know when the current regime of strong performance from the largest S&P 500 stocks flips, though we’ve seen hints of it since July 1st. What we do know is assuming trees grow to the sky and betting against history is a wager we’d rather not make. It can be boring waiting for the trees in the understory to catch up, but if past is prologue the wait can be well worth it.

Written by Alex Durbin, CFA, Chief Investment Officer